Je découvre Sindika Dokolo vers 2015, dans la revue Jeune Afrique que mon grand-père ramène régulièrement de ses bureaux parisiens de l’Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Son prénom évocateur et le statut de son épouse Isabelle Dos Santos, fille du président angolais, m’avait alors intrigué, l’origine de l’immense fortune du couple également. Dokolo est un protagoniste majeur du marché de l’art africain traditionnel et contemporain, ardent défenseur de rapatriement des oeuvres mal acquises ou spoliées, et promoteur d’une culture du collectionement et du développement culturel sur le continent africain par des acteurs africains. Je découvre alors dans les rares articles consacrés au couple que la famille Dos Santos est sous enquête pour corruption et soupçonné par certains de détournement de fonds publics aux plus hauts sommets de l’état, à la fois en Angola et au Congo. Ce matin d’octobre 2020, j’apprend enfin la mort de Sindika Dokolo lors d’un séjour de plongée à Dubaï, ce qui m’apparaît immédiatement suspect. Bien que l’accident réel ne puisse être exclu, d’importantes zones d’ombres subsistent, et Sindika Dokolo semble parti pour susciter autant de questions et de controverses mort que vivant.

Plus tard dans le mois, j’ai l’intuition de mentionner le nom Dokolo à deux nouveaux collègues, l’un compatriote congolais du milliardaire, l’autre d’origine ivoirienne et ayant exprimé sa politisation et son intérêt pour l’actualité politique africaine. Je ne sais pas si le sujet fera mouche. C’est en fait un succès au-delà de mes espérances, puisque l’un d’eux m’apprend même sur la famille Dokolo des choses qui n’étaient pas parues dans les médias occidentaux, notamment l’intérêt de la puissante famille pour la réunification de l’Angola et du Congo, projet dérangeant pour beaucoup mais trouvant un large écho auprès de la population congolaise.

Annonce de sa mort sur la page Instagram d’Isabelle Dos Santos @isabel_dos_santos.me

É com profundo pesar e consternação que a família Dokolo, esposa, filhos, mãe, irmão e irmãs, neste momento de enorme tristeza e dor, lamenta informar o falecimento de Sindika Dokolo, na quinta-feira, 29 de outubro 2020, no Dubai. A família agradece a todos os que expressaram sentimentos de pesar, solidariedade e bondade e que partilham a nossa dor.

La Famille Dokolo, son épouse, ses enfants, sa mère, son frère et ses sœurs ont la profonde douleur et l’immense tristesse de faire part du décès de Sindika Dokolo, survenu ce jeudi 29 octobre 2020 a Dubai. La Famille remercie par avance toutes les personnes qui prennent part à sa peine.

The Dokolo family, his wife, children, mother, brother and sisters have the deepest sorrow and immense sadness to announce the passing of Sindika Dokolo, which occurred this Thursday, October 29, 2020 in Dubai. The family would like to thank all those who have expressed their sympathy and kindness and who share our grief.

Sindika Dokolo, Crusader for Return of African Art, Dies at 48

He started a campaign to repatriate art stolen or removed during the colonial era. This year, he and his billionaire Angolan wife were embroiled in a corruption investigation.

By Richard Sandomir Nov. 11, 2020

Sindika Dokolo, a wealthy Congolese art collector who crusaded for the return of African art removed during the colonial era by Western museums, art dealers and auction houses, but who became embroiled this year in investigations into how his Angolan wife had acquired her riches, died on Oct. 29 in Dubai. He was 48.

His family announced his death on his Twitter account. According to news media reports, he died in a diving accident off the coast of Dubai.

“Works that used to be clearly in African museums must absolutely return to Africa,” Mr. Dokolo told The New York Times in 2015. “There are works that disappeared from Africa and are now circulating on the world market based on obvious lies about how they got there.”

Mr. Dokolo, who amassed a 5,000-piece collection of contemporary African art, established a foundation in 2013 that uses a network of dealers, researchers and lawyers working in Brussels and London to monitor the art market and scour archives for African art that might be repatriated.

When a stolen piece is tracked down, Mr. Dokolo told Artnet News last year, “we confront the current owner and we offer them two options: Either we go to court based on the evidence that we have, which means reputational damage, or we pay an indemnity, which is not the current market price, but the price they paid when they acquired it.”

His foundation has so far located 17 artworks and returned 12 to their rightful places. “If I have to spend a large deal of money and five years in court, I will do it,” Mr. Dokolo told The African Report in 2016.

His early recoveries include ancestral female masks and a male statue of the Chokwe people of central and southern Africa. They had been looted from the Dundo Museum in Angola during the Angolan civil war, which lasted from 1975 to 2002.

Mr. Dokolo had money aplenty to repatriate purloined African art. His father founded the Bank of Kinshasa in Congo during the dictatorial reign of Mobutu Sese Seko, and Mr. Dokolo was married to Isabel dos Santos, a daughter of Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who was the president of Angola from 1979 to 2017. A billionaire, Ms. dos Santos is said to be Africa’s richest woman.

In January, the Angolan authorities charged Ms. dos Santos with money laundering and embezzlement. Investigations by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 36 media partners, including The New York Times, showed how Western financial firms, consultants, lawyers and accountants had helped her profit from her father’s rule of Angola and move hundreds of millions of dollars in public money out of the country. The journalists were aided by 715,000 documents, called the Luanda Leaks, which were provided by a whistle-blower.The Year’s ObituariesRemembering Ruth Bader Ginsburg, John Lewis, Kobe Bryant, Chadwick Boseman, Kirk Douglas, Little Richard, Mary Higgins Clark and many others who died this year.Notable Deaths 2020

Ms. dos Santos’ assets, as well as Mr. Dokolo’s, were frozen in Angola, then in Portugal and the Netherlands, where they had business interests. The Angolan government is trying to recover about $1 billion in assets from the couple.

Mr. Dokolo had said that he and wife were scapegoats of the Angolan government, which is now led by President João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço.

“It does not attack the agents of public companies accused of embezzlement, just a family operating in the private sector,” Mr. Dokolo told Radio France Internationale in January.

Sindika Dokolo was born on May 16, 1972, in Kinshasa, Zaire (the former name of the Democratic Republic of Congo). His father, Augustin Dokolo Sanu, inspired his son to collect African art; his mother, Hanne (Kruse) Dokolo, was born in Denmark and moved to Congo in 1966 to oversee the Danish Red Cross dispensary there. She married Augustin Dokolo in 1968.

Sindika was raised in France and Belgium with his two sisters and a brother, attended the Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague in Paris and studied economics, commerce and foreign languages at the Pierre and Marie Curie University of Paris. According to his online biography, he left France in 1995 to be with his father and pursue family investments.

Mr. Dokolo and Ms. dos Santos married in 2002, bringing him to Angola, a Congo neighbor. Information about his survivors other than his wife was not immediately available.

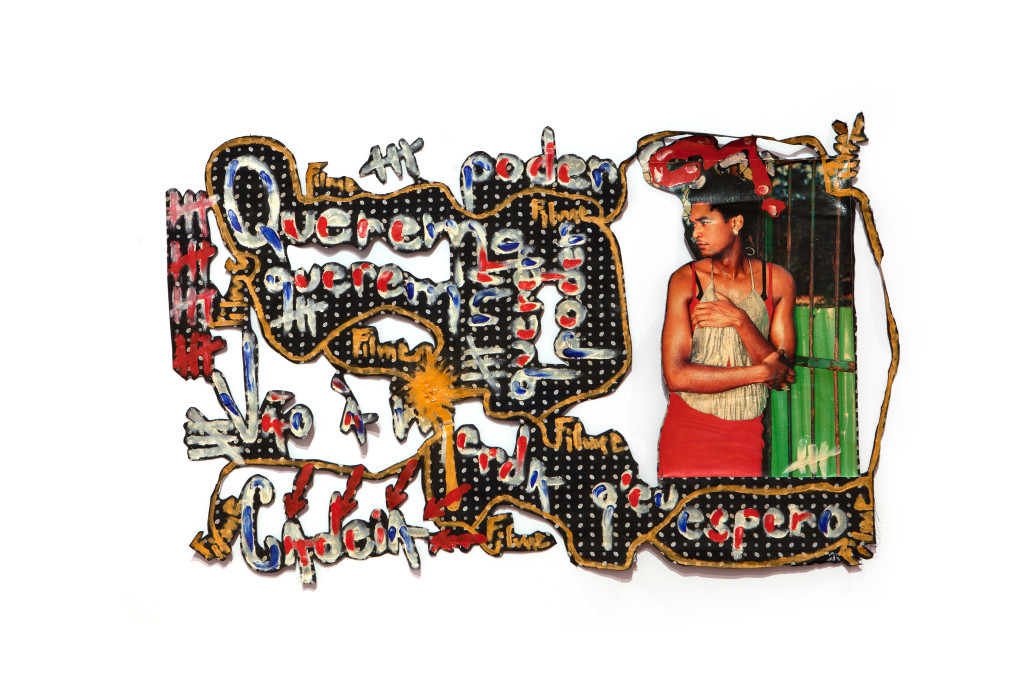

Mr. Dokolo’s vast African collection includes works by the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare and the South Africans Zanele Muholi and William Kentridge. He helped African artists show their work at Western events, lent some of his collection to the Venice Biennale in 2007 and gave 340,000 euros, through his foundation, to 17 artists who exhibited at Documenta, the German art event, in 2017.

But he seemed most passionate about bringing stolen art back to Africa, with a focus on his adopted homeland. Announcing the purchase of a Chokwe mask from a French dealer in 2016, he said, “Now is the time for all of Angola’s lost cultural treasures to return home, where they can play their role to the full; a role that will help strengthen Angola’s culture and knowledge.”

Correction: Nov. 12, 2020

An earlier version of this obituary misstated the name of an organization of journalists that tracked the actions of Mr. Dokolo’s wife, Isabel dos Santos, that led to charges of money laundering and embezzlement. It is the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, not the International Coalition of Investigative Journalists.

Congolese collector Sindika Dokolo reportedly dies in Dubai diving accident

Tributes pour in for “defender of African art”—who was also being investigated by Angolan authorities

by Anny Shaw, 30th October 2020, 12:14 GMT. Sindika Dokolo reportedly died while scuba diving in Dubai © Miguel Nogueira

Update: On 30 October, after this article was published, Isobel dos Santos posted the following official confirmation on Instagram: “The Dokolo family, his wife, children, mother, brother and sisters have the deepest sorrow and immense sadness to announce the passing of Sindika Dokolo, which occurred this Thursday, October 29, 2020 in Dubai.”

The death of Sindika Dokolo, the Congolese-born art collector whose business was under investigation for corruption by authorities in Angola, has been reported by several sources including the Portuguese Lusa News agency.

According to Congolese and Angolan media, Dokolo, 48, died in a scuba-diving accident in Dubai yesterday, although there has been no official confirmation so far. As reports began to emerge, Dokolo’s wife, Isobel dos Santos, posted a picture on Instagram of her, Dokolo and one of their children with the caption: “My love…”

Leading art world figures have begun to pay tribute on social media to Dokolo, who campaigned for the repatriation of art plundered from Africa, successfully locating 15 looted works in Western collections and negotiating their return. Speaking to The Art Newspaper in 2014, Dokolo said that righting the plunder of Africa’s heritage “should be no less urgent” than the restitution of art looted by the Nazis.

Today, Touria El Glaoui, the founder of the 1-54 contemporary African art fair, described Dokolo as “one of our most important defender[s] of African art”. She says: “So saddened by the loss of Sindika this morning […] All my thoughts and prayers are with his family. Our world will miss you.”

The Belgian-Congolese dealer Didier Claes, who helped Dokolo build one of the largest collections of African art in the world, says: “You had an ambition, that of being the first African to put together one of the most beautiful collections of African art in the world. You made your dream come true…”

Claes adds: “Sindika Dokolo was one of those art lovers who does not sleep, the very ones who contemplate objects for hours and with whom you can spend the night discussing a work […] The Congo is losing one of its worthy sons, the African art world is losing one of its greatest defenders and collectors, and I am losing a very great friend.”

The South African-born artist Kendell Geers says he was “deeply shocked” by the news of Dokolo’s death. He adds: “He was a beautiful, sincere, generous and courageous person, committed to his family and friends. He inspired me with with courage and gave me strength with his faith in art. The world is a darker place without his bright shining light.”

However, others have hinted at a murkier side to the story. Responding to reports of Dokolo’s death, Ana Gomes a former European Parliament member, wrote on Twitter: “Strange. Very strange …”. In November 2019, Gomes filed a complaint in Portugal against Dos Santos, alleging that she laundered money siphoned from Angola through the Portuguese firm Banco BIC.

Dos Santos, the daughter of José Eduardo dos Santos, Angola’s former president, and the richest woman in Africa with an estimated fortune of more than $2bn, has been accused of exploiting poverty-mired Angola, taking a cut of the county’s wealth and parking it abroad with the help of an elaborate web of lawyers, bankers and accountants.

According to a vast investigation published in January this year by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) dubbed the Luanda Leaks, more than 400 companies and subsidiaries in 41 countries were found to be linked to Dos Santos or Dokolo, including 94 in secrecy jurisdictions such as Malta, Mauritius and Hong Kong.

The same month, the Angolan government froze Dos Santos and Dokolo’s assets and bank accounts in a bid to to recover $1bn in state loans Dos Santos allegedly borrowed and failed to repay during her father’s term in office. In March, a Portuguese judge ordered the seizure of all assets owned by Dos Santos in Portugal, although it is not known whether this covers Dokolo’s 3,000-strong art collection, which includes contemporary pieces by William Kentridge, Zanele Muholi, Edson Chagas and many more.

Dos Santos has vigorously denied any wrongdoing, labelling the charges against her a government-contrived “witch hunt” designed to destroy her reputation and deflect from Angola’s current economic problems.

theartnewspaper.com/news/congolese-collector-sindika-dokolo-reportedly-dies-in-dubai-diving-accident

information.tv5monde.com/video/deces-de-sindika-dokolo-c-etait-un-homme-engage

The artwashing of Sindika Dokolo?

by Delinda Collier + Marissa Moorman

Coverage of the #LuandaLeaks revelations have steered clear of the art world dealings of Isabel dos Santos’s husband, and art luminaries have largely defended Dokolo’s reputation.

Sindika Dokolo is reputedly the biggest collector of African art and also its most generous patron. Dokolo is also seen as a leader in the movement to repatriate stolen African art and artifacts from Euro-American institutions to African ones. And he is the husband of Isabel dos Santos, celebrated as Africa’s richest woman and a longtime target of criticism by Angolans, like investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais and now #LuandaLeaks, for her corrupt business dealings and large scale theft from the Angolan state. (She got her start as daughter of Angola’s longtime former president.) What has been striking thus far has been that coverage of the #LuandaLeaks revelations, and previous investigations of dos Santos, have steered clear of Dokolo’s dealings in the art world and luminaries in that world have largely defended Dokolo.

If you missed it, #LuandaLeaks, which broke last Sunday, show how Dos Santos and Dokolo “were allowed to buy valuable state assets in a series of suspicious deals” that personally benefited them and cost the Angolan state and taxpayers millions of dollars.

That little connection has been made between #LuandaLeaks and Dokolo as art patron and activist, may because of his own PR. Dokolo articulates his efforts to investigate and repatriate stolen art objects to African nations in a decolonial discourse that distances him from global systems of economic injustice. To be sure, he is unique in the world of collecting, fashioning himself as both a member of the elite and a postcolonial activist who has made good on his talk about restitution, even as he propagandized it. He promotes this image in countless media interviews and on his own social media. Take a recent Instagram post by Dokolo. His foundation had bought space on the NASDAQ electronic billboard in Times Square in New York City, highlighting his work repatriating African art. The Instagram video of the billboard is accompanied by this comment by Dokolo:

#GiveBackOurArt. We repatriate African art to museums in Africa. African art is our history, our identity, our dignity. My history didn’t start in 1482, the 1st time a Portuguese explorer set eyes on a subject of the Kongo kingdom. I was there before, I was there all along.

Will the #LuandaLeaks story cast his narrative in a new light?

The launch of #LuandaLeaks has sent Isabel dos Santos, the Angolan government, international banks, accounting firms and bankers scrambling. The Sindika Dokolo Foundation website is suddenly “undergoing some maintenance.” On the eve of the World Economic Forum, organizers removed dos Santos’ name from the list of participants gathering this week in Davos, Switzerland. EuroBic – a Portuguese bank in which dos Santos is a key shareholder – announced it would sever all ties with her. The London-based global business services firm Pricewaterhouse Coopers did the same. The head of its Lisbon office’s fiscal and audit department, Jaime Esteves, went so far as to step down, citing the “seriousness of the Luanda Leaks allegations.” The Angolan Attorney General, Helder Pitta-Grós, said the Angolan judiciary is working to bring them back and to pursue action against dos Santos and Dokolo for using state money for personal profit. As global businesses and their leaders avert their eyes, cut links, and publicly declare their distance from dos Santos and Dokolo, the art world seems to be taking a wait-and-see-approach.

Luanda Leaks has not left Dokolo unscathed. Still, no one has raised the implications for Dokolo’s art collecting and art restitution campaign. The French newspaper, Le Monde, reports, that for the most part and for now, Dokolo’s associates in the art world are standing by him. Le Monde quotes Simon Njami, a leading curator of African art in Paris and who Le Monde identifies as a former art advisor to Dokolo: “I refuse to scream with wolves. As far as I know, Sindika was not a dealer in weapons or drugs. As far as I know, he did not manage national companies. Until further notice, what I retain from him is that he has advanced contemporary art in Africa and I keep all my respect for his action.”

Most of his art-world colleagues find Dokolo sincere in his love of art; they seem willing to separate his profile as a collector (and now curator) from any allegations of financial wrongdoing with his spouse. Anna Alix-Koffi, a French-Ivorian magazine publisher and curator, told Le Monde: “Do you know many people who would buy works for hundreds of thousands of euros to return them to their country? He is a defender of African art and, as such, I am by his side.” Further, they tend to believe Dokolo’s now-undermined claim that his money and interests are separate from Isabel’s.

Here’s the problem: of course, we fully support the restitution of African art, the expansion of art scenes on the Continent, and rethinking museums, but we question whether the economic system that makes Dokolo’s work possible comports with the social benefit of art repatriation. If African art becomes an empty symbol of decolonization, it risks becoming a fetish once more.

It is also the case that Dokolo’s aggressive publicizing of his efforts tends to obscure the years-long effort to repatriate Angolan art that preceded him. Dr. Nuno Porto has written about the risks and rewards of those efforts for many years. As art institutions become nearly totally dependent on philanthropy, the restitution of African art risks becoming a PR maneuver for political or business ventures, a practice that has garnered its own neologism: “artwashing.” Philanthropy underscores the power and glamor of giving, whether it is George Clooney, Oprah Winfrey, Bill and Melinda Gates, or Mo Ibrahim. However, the bright lights and bling of giving obscure the almost total non-transparency of philanthropy. The purported “good” of art to society is completely undermined by the lack of the very “public” scrutiny that is required of policy work. We should all worry when private money replaces public policy.

Dokolo has worked with the Angolan Ministry of Culture, advocating a mixture of public and private funding that carries the risk of the philanthropists losing their financial stability or shifting their focus. State entities are tasked with collecting and displaying cultural heritage and the terms are clear: it belongs to the public and should be a visible part of public life. The MPLA, Angola’s ruling party since independence in 1975, was clear about this public ownership of art in their many statements about culture and art after independence.

#LuandaLeaks gives us an opportunity to consider the privatization of public goods, whether Sodiam funds, loans from Sonangol, or artworks. This is a story that should make us all uneasy; it braids together kleptocracy, philanthropy, and a discourse of decolonization. Dokolo and dos Santos argue that Africans are often unfairly singled out as corrupt, despite their use of this fact to deflect scrutiny. And they aren’t wrong. There is talk about trouble at PwC, but reporting shows that attention clings to dos Santos and Dokolo more readily than to the accountants, especially Western ones. Accounting and business service firms facilitate and regulate the global economy, crafting tax shelters and offshore accounts, but they tend to not have exciting public images or much of a presence on social media platforms. Yet we might do well to think of them as Hannah Arendt imagined German bureaucrats under Hitler: accountants make theft banal. These European and American firms helped dos Santos and Dokolo launder the money, like much of the art world is now called to do. Dokolo’s repatriation efforts and his patronage of African artists, no matter how sincere his interest, clean up his image while making art dependent on dirty money. This is why his art world and academic collaborators are so quiet. But just as the pressure mounts for museums worldwide with campaigns like #decolonizethisplace, the time may be up for revolutionary rhetoric funded by illicit gain.

africasacountry.com/2020/01/the-artwashing-of-sindika-dokolo

Interpol seeks arrest of Angolan tycoon Isabel dos Santos | Crime News | Al Jazeera (1 dec. 2022)

How Angola’s Isabel dos Santos stole a fortune: ICIJ documents (20 jan. 2020)

La milliardaire Isabel dos Santos visée par une myriade d’accusations par la justice angolaise. Agence France Presse citée dans le Journal de Montréal, 23 janvier 2020.

courrierinternational.com/article/angola-luanda-les-caprices-de-la-princesse-isabel-dos-santos

Sindika Dokolo, né le 16 mai 1972 à Kinshasa au Zaïre, est un collectionneur d’arts et un homme d’affaires. Il détient la plus importante collection d’art africain contemporain, maintenant environ 5.000 œuvres d’art.

Collectionneur d’art

Sindika Dokolo a commencé à l’âge de 15 ans à construire une collection d’œuvres d’art. Dans une interview à la chaîne de télévision angolaise TPA, il a dit que ses parents aimaient beaucoup l’art: sa mère lui a fait visiter tous les musées d’Europe et son père était un grand collectionneur d’art africain classique.

Sindika Dokolo a lancé la Fondation Sindika Dokolo dans le but de promouvoir de nombreux festivals artistiques et culturels. Sa mission est de bâtir un centre d’art contemporain à Luanda qui ne servirait pas seulement à l’exposition d’œuvres, mais également à l’incubation d’artistes locaux et internationaux. Sa collection d’art, la collection Dokolo, réunit 5000 œuvres d’art signées par plusieurs artistes. Sindika affirme que son rapport avec les arts n’est pas destiné à être reconnu comme un grand collectionneur, mais plutôt “montrer des artistes africains dans le monde”.

Afin d’exposer au public africain la production artistique contemporaine, Sindika Dokolo a conduit sa collection à Luanda, à des événements réguliers, en particulier avec la Triennale de Luanda. La Fondation Sindika Dokolo est responsable pour la participation du premier Pavillon Africain à la Biennale de Venise en 2007.

En décembre 2013 Sindika a assisté à l’ouverture de la VII Biennale de Sao Tomé-et-Principe, exposition internationale d’art dans ce pays, où sont exposées les œuvres d’art de la Fondation Sindika Dokolo. Dans une interview avec le journal portugais Jornal de Negócios, le collecteur d’art parle de sa collection, et considère que “l’avantage de la scène artistique africaine contemporaine est de donner une perspective sensible et intelligente d’un continent en pleine mutation”. Dans la même interview, Dokolo souligne que “en termes démographiques, en 2050, il y aura 25% plus d’Africains que de Chinois, et dans le plan économique on assiste à un croissement économique structurel du continent africain”, aspects qui, selon lui, vont projeter le continent africain dans le futur.

En mars 2015, la mairie de Porto a décerné à Sindika Dokolo la médaille du Mérite à l’occasion de l’exposition d’art contemporain “You Love Me, You Love Me Not”. L’exposition comprend des œuvres appartenant au collectionneur d’art et réunit une cinquantaine d’artistes.

Homme d’affaires

Installé à Luanda depuis 1999, il rejoint les fonctions d’homme d’affaires, d’opérateur culturel et de président de la Fondation Sindika Dokolo.

Sindika Dokolo possède plusieurs entreprises en Angola.

http://www.fondation-sindikadokolo.com/en/sindika-dokolo/

He is a member of the board of the Angolan cement company Nova Cimangola. Sindika Dokolo is also a member of the board of Amorim Energia that owns a third of the Portuguese petrol company Galp through the company Esperanza Holding BV.

The art collector has also invested in various sectors, including diamonds, oil, real estate, and telecommunications, in Angola, Portugal, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Mozambique. In an interview with Jeune Afrique, he also stated that his aim is not “to build a large integrated group”, but rather to have the opportunity to see “Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo as a complementary complement” – “a Luanda-Kinshasa axis that could create a counterweight to South African supremacy”.

In 2020, leaked documents indicated that Dokolo had made millions from a suspiciously one-sided partnership with the Angolan state diamond company, Sodiam, to buy a stake in Swiss luxury jeweler De Grisogono.

peoplepill.com/people/sindika-dokolo/

icij.org/investigations/luanda-leaks/explore-how-to-build-a-business-empire/

On Dec. 23, 2019, an Angolan court orders the freezing of Isabel dos Santos’ and Sindika Dokolo’s assets. She labels the court order “politically motivated”.

Decade-International-Isabel-Dos-Santos-Approval

Consulter les documents des Luanda Leaks

Angola : la princesse Isabel Dos Santos contre-attaque (mai 2021)

”Isabel dos Santos s’est procuré des enregistrements secrets de certains membres de l’élite politique angolaise en faisant appel à Black Cube, une agence de renseignement privée fondée par d’anciens agents du Mossad, les services secrets israéliens.

Elle a remis ces éléments et d’autres documents à un tribunal londonien à la fin de mars [et a porté plainte contre son ennemi, le président angolais]. Ils montrent selon elle que João Lourenço a donné l’ordre à des juges, des procureurs et même des espions angolais de lancer des actions judiciaires et une campagne politique afin de mettre en terme à son empire. Isabel dos Santos accuse en outre le président angolais de se livrer à une campagne de “vengeance personnelle” à son encontre.”